"I've never seen them focus that intensely. They asked if they could do it again the next day." --Ann Ashley, the students' classroom teacher

Here is a video of me teaching an art lesson this last week at Kula Elementary School in Maui, Hawaii (my old elementary school!)

These 5th graders learned a new way to draw people, one that allows the students to draw people in just about any position they can imagine. They made use of anatomy, proportion, and measuring using units. I have taught versions of this lesson to students as young as 2nd graders. Guided by the questions of these older students, we expanded off the basic lesson to include concepts such as foreshortening and complex poses.

Here are the time marks for interesting moments in the lesson:

These 5th graders learned a new way to draw people, one that allows the students to draw people in just about any position they can imagine. They made use of anatomy, proportion, and measuring using units. I have taught versions of this lesson to students as young as 2nd graders. Guided by the questions of these older students, we expanded off the basic lesson to include concepts such as foreshortening and complex poses.

Here are the time marks for interesting moments in the lesson:

00.00 Introduction, student exampleAt the end of the movie the students return to work and put their ideas from the gallery walk to use. They continued to draw for another 20 minutes. Students fine-tuned body positions, added backgrounds, and shading. In the last 5 minutes we looked at the completed artwork at a circular table, allowing students to gather around and share about their work.

2:18 Look at Da Vinci's sketches and talk about anatomy

4:20 What is Proportion?

6:04 What can we use to measure our body? (Students try several ideas.)

8:08 How many heads tall is your body? (Students measure with partners, we record answers, guesstimate a class average.)

10:14 Drawing demonstration using proportion and simple anatomy.

16.24 Students think about the body position they will draw, stand up and pose.

18:27 One-on-one, answering advanced questions that lead to learning about foreshortening.

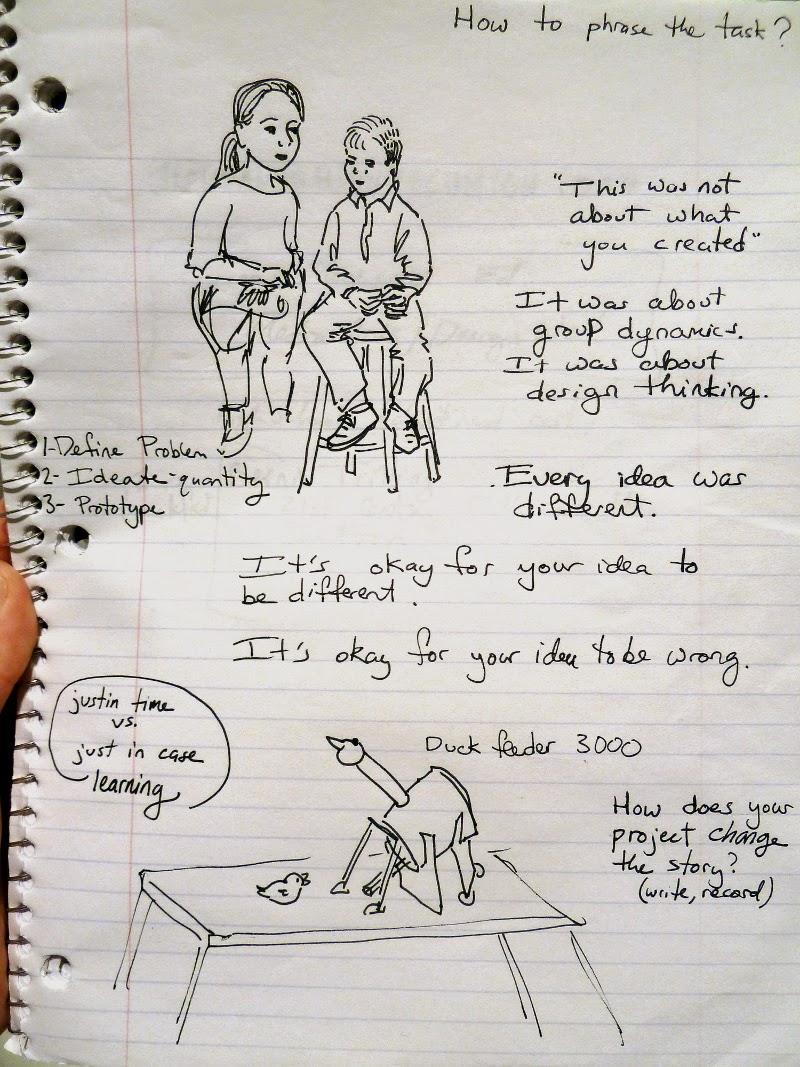

20:25 Midway conversation: What can we look for in a gallery walk?

23.54 After the gallery walk: What interesting choices did you see? Which of your challenges did you find solutions for by looking at classmates work?

What I love about this project:

Between 3rd and 5th grade students begin to look for a way to accurately draw what they see in their mind. This lesson gives a set of steps that all the students seem to find accessible and useful for drawing people doing things. (Note: I always state that this is one way to draw people, not the only way. I want them to feel good about their personal drawing styles, even if I'm asking them to follow certain steps for this project.)

My experience has been that students are excited to use these techniques to express their own experiences, create fictional characters such as superheroes, and to illustrate concepts. Teachers report back that students continue to use this process without prompting in classwork drawings, as well as to draw in their own free time. It becomes a tool that enables their creative and academic expression.

This student chose to illustrate a scene from a favorite Animorphs book and include dialog in the drawing.

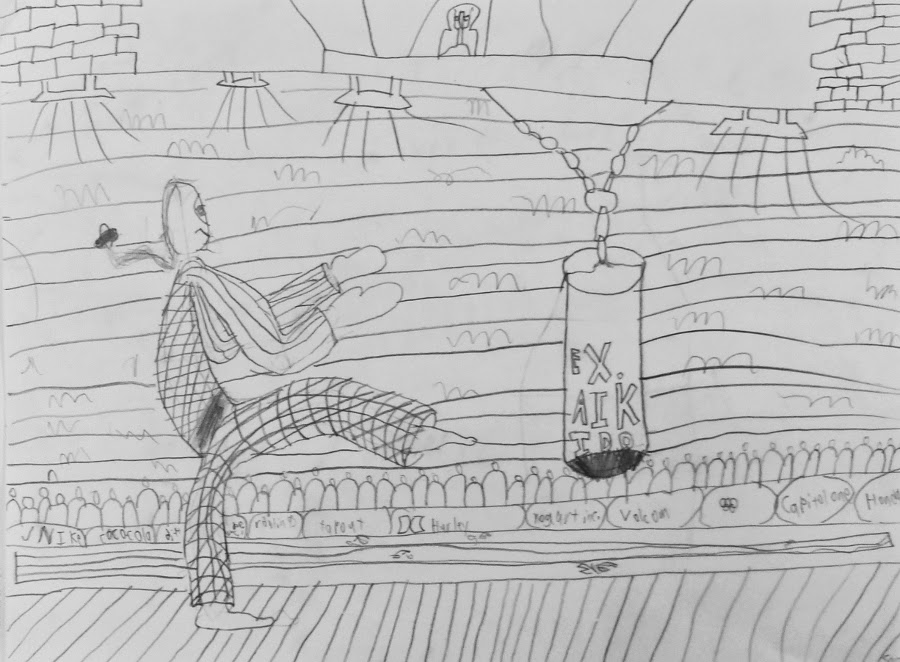

A martial artist performing in front of a crowd

A weightlifter in a gym

Tether ball

Playing baseball in the rain

The student attempted a challenging sideways pose.

Playing soccer, with a fantastic background